Richard Price’s new novel Lazarus Man was released on November 12th. This past Friday Price sat down with me at his home in Harlem for an interview (our second, after our previous conversation in 2016) about the new book, his TV projects, family life and more.

Me: You just released your new novel, Lazarus Man, and I know you’ve been working on that since 2008, I believe. So can you talk about how this project has evolved over the years?

Richard Price: Yeah, slowly. 2008, it’s on a contract. Right after Lush Life, for [publisher] Farrar, Straus. You know, to do another book. 2008 was kind of a tumultuous year.

For you personally?

RP: Yeah. Moved up to Harlem. There was personal stuff–you know, nothing lurid, but I’d rather not talk about anything that involves other people. But I was with Lorraine [Adams, now Price’s wife], and it was a new relationship. It just took like two years to just get settled from that vibration. And when I started writing, I also needed money, so I needed to go off. Nobody gets–you’re not going to live on royalties of a book. So I do my thing, I do my TV pilots or screenplays. And COVID happened, and some of these pilots got picked up into series, which was, you know, all hands on deck, don’t even think about doing anything else. And this, that and the other. And I was kind of afraid of the book at first. I was sort of feeling around it. So it wasn’t until the writer’s strike that I realized, if I don’t do it now, I’ll never do it. You know, the joke I always tell is, if it was a baby in 2008, it would be applying for college now. So yeah, this is long, but it’s not like I was doing nothing else. You know, I wonder as I wander. I was working and dealing with changes, and I’m just really glad it’s out.

And I know the book is about Harlem, and you started it when you moved here. Did you have a personal connection to this area before then?

RP: Well, listen, as a stretch I could say, well, my grandmother was born in Harlem, in Jewish Harlem, and one of my uncles had a gas station in Harlem. But that’s bullshit, in terms of… That’s really grabbing at straws to say, “Oh, I’m an old Harlem guy.” But part of what slowed me down is that because Lush Life was kind of a panoramic portrait of the Lower East Side at the beginning of its gentrification, I wanted to do something panoramic about Harlem, but look, you just got here. What do you know? What you first feel like is everything is like, “Wow. Oh my God. Wow, wow, wow.” And you can’t write a book called Wow which has only one word in it, “Wow.” So I had to just live here. I just had to absorb where I was until the wows became “Oh, that again.” Which is to say, I started recognizing things as opposed to being mindblown by things. And it took a long time until I felt my knowledge of this area was nuanced enough. Otherwise it would be a Fodor’s Harlem on $5 a Day book if I wrote it when I intended to.

So I just had to live. The book had to breathe, and I just can’t force it. It’s like when I was teaching various writing classes in MFA programs or even undergraduate, I just–what can I teach? You’re young, you’re like 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, and it’s like, what do you know? You don’t know… You could be talented and you could be clever and and have great style, but the substance–why should I read you? What do you know that I don’t know? What am I going to learn from you? I don’t want to outstrip you as a reader, in terms of, like, “Nah, that’s not it.” The only thing I could do for my students is give them a magic pill that would make them 35 instead of 19, or 40 instead of 20, so they have, you know, life–life is like being here and trying to figure out how to write about a place. You gotta live. You gotta live, you gotta get a job, lose a job, get married, get divorced, have kids. You just gotta live.

So that’s a lot of what slowed it down. And also my aversion to writing. I’d rather do anything but write, because for me–it sounds coy, but I’d just much rather be on the street talking to people. On one hand, it’s quote unquote “material.” On the other hand, it’s avoiding writing. At some point you gotta write.

Yeah. And I know you said that you were working on this book when the pandemic happened, and you’ve said that was a difficult time for you because you couldn’t be out observing people in the same way. Can you talk a little more about what the pandemic was like for you and how you dealt with that whole situation?

RP: Well, other than the general fear it put into everybody and the paranoia–I mean, I was no different than anybody else. My wife is no different than anybody else. But basically it was, I can’t do my thing, you know? And not to minimize the impact of COVID, but for me, professionally… It’s like, people–”Oh, we can’t get to the office, there is no office for two years.” Well, this is not an office. I’m in my office. This house is my office. I can’t go out in the street, I can’t leave my office so I can go back to my office and write. And I had to remind myself, “It’s fiction. You can make things up.” But just as a habit, I was so reliant on just getting out. Lorraine came up with the phrase “reporting the novel,” which is, you’re not writing journalism, but you’re seeing the seeds of truth. And you don’t have to be accurate. You just have to be plausible. It’s amazing how… I always felt like you have to do such deep research to write about things that you don’t know first-hand. But basically, it’s like you get this feeling of like, just give me enough that I can take it from there, and whatever I write will not embarrass you because it’s so off the mark, you know? So I just like it better. I just like going out there. Nothing worse than a blank page.

The book is set in 2008 also. What made you settle on that time period?

RP: Because I wanted to get the sensibility which was much less politicized than it is right now. This is before a lot of policing of language, a lot of policing of who’s allowed to write about what. It was before Black Lives Matter, it was before Trump, before so many things. And Harlem, like the Lower East Side in the time period that I wrote about it, was in a state of flux. And it had been for a couple of years before, but it was slow going at that time. A lot of what was in Harlem in 2008 is no longer. So I could say even in my life, “Well, Harlem’s changed, you know, since–” What am I, an oldtimer? But it has. And I’ve witnessed that, and I’ve tried to capture that. I didn’t want to shit on gentrifiers, you know, yuppies, buppies, muppies, whatever they are now. I didn’t want to cast anybody as a particular villain. For me, even if they were villainous, they have to have complexity to them. And I just felt like it was too easy to dump on gentrifiers.

Sure. And it sounds like you’re happy to have the book out at this point. Having worked on it for as long as you did, do you have a sense of loss also?

RP: I have a sense of great relief. And a new worry: Now what? No, I don’t have a sense of loss. This book, like any other book, is part of my legacy. It’s part of what I pass down to my kids and the culture. So nah, I’m good, I’m good. I just wish I had another book, like, now, you know?

Well, I was wondering about that. Now that this is out, do you have an idea of what your next thing is?

RP: Well, my next thing is making money. Normally when I didn’t even have money pressure it just took me a couple years between books to figure out what I want to write about. I’m like the opposite of a book a year guy. I assume it’s once again going to be something involving an urban area, northeast, probably New York again, but… And I don’t want to write a historical novel. I don’t want to write about, you know, something in Colorado simply because I want to demonstrate I’m not a one-trick pony. After a while, you write what you want to write. Where you go is where you should go, for me. Anywhere else I would be talking back to somebody. “Oh yeah? Well, how about this? Yeah, well, wait for my book to come out on the Spanish Inquisition. Just hold your breath.” No, I’m happy here. And this is where–I feel like I’m still learning. I still feel like a student in the best way. And that just sort of keeps me vivid to myself. I’m as eager as I’ve ever been to explore something and let it hit or miss me when I get home. So that’s the fun part.

Well, I wanted to ask you about some of the TV work that you’ve done since the last time we spoke. I know you were an executive producer and a writer on The Deuce. Based on your writing credits, it seems like you sort of got less involved as it went on…

RP: Well, that was the policy that we… Dave Simon decided there’s going to be no “Co-written by.” You know, you want to give the younger writers a chance. And even though you might be doing work on these episodes, you’re not going to get credit because it’ll take away–this is their step into the Writers Guild or something. Why water it down when you don’t need it for yourself, really? I mean, if I’m the sole writer on it I’ll get writing credits. But I just felt like, my job was more or less to be a ghostwriter and sort of a cleanup man, like a script doctor.

And you were doing that throughout the run?

RP: Yeah.

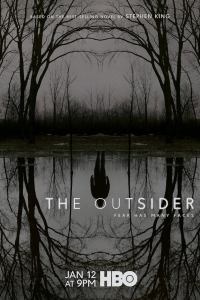

And you were also the showrunner on The Outsider…

RP: Well, let me tell you something, I was not a showrunner. “Showrunner” implies somebody who has the big picture. Nuts and bolts stuff. I’m a writer. That’s all I do. And somehow the word “showrunner” came up, and it’s a misnomer. I’ve never done any showrunning. All I’ve done is writing and rewriting of other people’s work. “Executive producer…” It’s kind of a sop. It doesn’t mean anything. My television could be an executive producer. It’s something they give you to sweeten the deal. It’s just a credit on a TV screen. There’s no guild for executive producers. It’s like pencil sharpeners. It’s a vanity thing. And it’s nice to see your name more than once when something’s playing on TV. You know, “Written by. Ooh, executive producer!” It’s bullshit. I mean, for the most part. Some people really are executive producers in the sense that they contribute to the production beyond getting the scripts ready. Either financially or actuarially or… They do something I can’t do.

Yeah, but you wrote most of it. I would imagine it’s a pretty all-consuming job, to work on a whole season like that.

RP: Well, it depends. We were talking about The Deuce, so…

Yeah, with The Outsider, though…

RP: Oh, The Outsider. No, no, no. The Outsider… I wanted to do it all by myself, and HBO said, “Timewise, you won’t be able to do that.” So there were two other writers and basically I did a lot of rewriting for one and less rewriting, but rewriting nonetheless, for the other. And frankly, it would have been more efficient… When you have a script and you’re going, like, “No, no, no,” then it’s like this interweaving that takes time, you know? I think it would have been faster if I just had a blank page and I started from scratch rather than this. But once again, the production speed–you have something like three weeks or less to shoot an episode, probably less. Meanwhile, they’re already prepping for the next episode, which hopefully you have written, but if not, it’s like Charlie Chaplin in Modern Times when he’s on the assembly line and he’s just sniffing cocaine, that’s what it’s like. “Oh, I’ll do it all myself.” Well, good luck, I hope you don’t break anything.

I know when you were promoting The Outsider, you said that you’ve been a “secret horror geek.” I’m a big horror fan myself, so I wanted to ask–

RP: Oh my God, I could show you some of my horror collection upstairs.

I would love to see it! I mean, what got you into the genre, and what’s your relationship with it been?

RP: It starts with pre-adolescence. I just love spooky… I would buy these cheap horror anthologies from like Ballantine Books or Ace Paperbacks or Signet. I just always had a sweet tooth for that stuff. And I’ve always wanted to write something that could be called horror, but wasn’t horrible. The problem with horror is that what you read is rarely horrifying. I mean, “thriller”–”Well, I don’t know. I wasn’t exactly thrilled.” There’s these words, but were you thrilled? Were you horrified? Were you frightened? “I was interested in it. It kept me going.”

I had had an experience with… It was before Lush Life. I had decided I wanted to do something with that genre. And I wound up being hooked up with a cabal of Wiccans. Not a cabal. Wiccans, but they were regular working class people. There’s four of them, five of them. And somebody tipped me off to this woman who… There used to be a bookstore on West 18th Street called The Magickal Childe, and they spelled “magical” with a CK and “child” with an E at the end. And so you’d go in there, “Can I have a geode?” But in the back there’s this lady that, for a couple of bucks, she would do a tarot card reading. And we got to talking, and I told her what I was up to, and she said, “Oh, you should come to our meeting.” And I went. And it’s just working class people there, and they had a Ouija board. And they said, “Who is no longer here, but you would like to have one more conversation?” So I came up with my cousin, who died at 26, when I was 11. He died of an overdose. And they started–”Okay, he’s here. Ask him questions.” “Who’s your mother?” And the two women on the planchette: “M… A… R.” How they did that, I don’t know, but his mother’s name was Martha. After about five more questions they had me so convinced he was in the room, that I was talking to him. And his responses to my questions got angrier and angrier, and I was scared. You know, “Your brother Stanley is still alive, Paul. Do you want me to give him a message?” “Tell him I hate him. Tell him I hate him.” And I’m going, “I can’t do that, I’m not going to–” He said, “Tell him, tell him, tell him!” Over and over and over. And I was shaking. “Oh, so you wanted to experience something horrible?” So I really wanted to write something about that.

But Stephen King’s book is about–the content is the content. For a second season, I wanted to do something more about what I just told you. HBO commissioned it. The pilot had a writer’s room, this that the other, laid out a story and everything, and they decided not to do it. So anyways, I did The Outsider.

I was going to ask about that, because I know that and The Night Of, it seemed like they were really successful. But as far as you know, there’s no current plans for additional seasons to those?

RP: No, I think what happens with a series that’s based on a popular book is that once that book is told, they’re less likely to go on without the book. Like, “Imagine the second book of this.” But there is no second. There is no Stephen King sequel to that. And once Stephen King is gone, it’s more risky.

I think I asked you about this last time, but since I guess 2016, have there been any film or TV projects that you’ve done uncredited script work on that people might not know about?

RP: Since 2016? God, I don’t even know what year it is. The older you get, the more you’re horrified by the arithmetic. “2016, what was that, 3 or 4 years ago?” “No, nooo, it’s ten years ago!” says the skeleton with its scythe and black wings. God. Let’s see, what did I do? After The Outsider–well, The Night Of? I can’t even remember what year that was.

Last time we talked was like right when that was coming out.

RP: Okay. Night Of, The Outsider, working on The Deuce… I don’t know, I can’t remember. I know I didn’t write any novels at that time. Basically, I did the writing that would pay the bills. It was fine.

To take a broader perspective, the whole film and TV industry over the last several years feels like it’s been in upheaval with kind of the bursting of the streaming bubble, and the strikes, and there’s this idea that everyone’s going to get replaced with AI. As someone who’s worked in this field for several decades, how do you see the industry as having changed over the last few years?

Well, I don’t keep an eye on the industry. I really isolate myself. I feel like, “What’s my job? Okay, I’m going to do it.” I know a lot of people–obviously, what you said. They’ve noticed that there’s a certain ruthlessness and less of an appetite for anything that’s challenging. More family-friendly. And I hear, you know, this streaming service is in trouble, that streaming service is in trouble, what’s the next shift in the paradigm? I hear that, like, fifth-hand. I don’t get involved in that.

For example, The Whites was originally sold to Sony. First I did a feature film script for it–

You did?

RP: Yeah. And it didn’t work. There were too many characters, too many secondary characters, too many cross-references. You can’t do that in a two-hour film. It was Scott Rudin and Sony. It went from there to somewhere else… Oh, then HBO picked it up. And I wrote the pilot. I love episodic TV because it’s more like a book. Every episode is like a chapter. You have all this leisure time to develop the characters and not just be [going] screamingly from event to event. You know, it’s like I say, speed chess. But I wrote the pilot and a second episode for HBO. Everybody loved it. And what happened was, whoever was in charge had a mandate: “Why are we watching this particular fill-in-the-blank right now?” And the theme of it was gentrification is violence. And it took place in–I can’t even remember, 2008, contemporary–but this is like, eight, ten years later, and he said, “Well, that was ten years–” No, it’s gentrification! It’s not like, you know… It’s here, it’s now! This is the ur-gentrification story. But, couldn’t get past that. And it got to the point where I said, “Well, gee, I guess I should make it more topical. Should I put in something…” And I mentioned some hot ticket of the moment, as a joke. And they said, “That might help.” And it was like, fuck me.

So that went the way of all flesh. Then somebody picked it up–I think Amazon picked it up? No no, Showtime. Then it went to Showtime. It was like an orphan going from foster home to foster home. And then it went to Showtime. Ethan Hawke was involved, he was a producer, he was going to be the lead actor. They scouted locations. They were all set with four days to go. Paramount brought in a guy to eviscerate Showtime so they could get rid of all the stuff that was too top-heavy for them, a.k.a. drama. It’s like in the old days, the Kansas City Athletics in the ’50s–basically it was a farm team for the Yankees. So this is like, Showtime is a farm team–who are the Yankees going to pull out of this? And then the Kansas City Athletics can go back to their poor obscurity. And so four days before they were going to start principal photography, the guy said, “No more cop shows.” And it died right there. And it was a ton of money coming my way if they actually packed the camera. And now, who’s got it now? I think Amazon’s got it now, but I don’t even ask. It’s like, you know, surprise me.

But that could still happen.

RP: Hypothetically. I haven’t heard anything. I didn’t write the scripts, I couldn’t write the scripts because of some legal thing with Sony. They brought in a British playwright, Jez Butterworth, who wrote–I think he won a Tony for a Broadway production. He’s a theatrical guy. And he wrote the scripts. So I haven’t even–I glanced at the pilot, but I haven’t read any of the other scripts. So they have a whole–it’s there. All they got to do is say, “Well, let’s do it,” or “Let’s see, maybe we could torture Jez Butterworth a little bit. Well, you know, times have changed, you know, this stuff… Why don’t you put something in about…?” So, you know, like Joan Rivers said about pregnancy: Knock me out, in three months wake me up when my hair is done. You know, bye bye. If I wake up and all of a sudden a little Tinkerbell fairy drops a check on my sleep mask I’ll be very happy, but if not I’m not going to think about it.

On a personal level, I understand that you’ve become a grandfather for the first time.

RP: Yeah, I have a five-month-old granddaughter, and my other daughter is due around Christmas. Listen, every kid is like, “Oh my God, this is the best kid in the world,” why? Because you’re not changing the diaper, you’re not waking up in the middle of the night. You’re grandparents. But I never wanted to be called grandpa because I know what my grandpa looked like, and… So my daughter decided to call me “Bookpa,” which I thought was hilarious, so I said, “Yep.” But then again, once the baby can speak it’ll probably go, “Buub.” And that’ll be my name, Buub. “Oh look, Buump Richard,” you know?

But listen, I have two daughters. I went through it. But now when I go over there, I can really watch the evolution, you know, from homunculus to baby to infant… And it’s delightful. The only problem is my daughter–I’m up here in Harlem, my daughter lives in [redacted for privacy], and it’s like an hour and change by Uber. But at least she doesn’t live in Poland or something.

That’s right around where I live. It’s a very nice area. I’m in [redacted], but…

RP: Oh right, right. Yeah. I don’t know that part of Brooklyn at all. I know Brooklyn Heights, like every yuppie parent. One of my kids went to Saint Anne’s. When I was a kid my grandparents lived in New Lots, which is… Linden Boulevard and Pennsylvania Avenue, and even in the 1950s, my grandfather, when he left the house, he used to take his wallet and slip it down the back of his shirt, because the odds are you are going to get braced, and if you don’t have a wallet they’re never going to find it in the small of your back. So it was bad then. But there’s two extremes of Brooklyn, New Lots and… But yeah, I’ve been out to [redacted], it is really nice. It’s very human, substantive. My other daughter lives on [redacted], so at least that’s closer.

Well, congratulations to you and your daughters. That’s most of what I have. The last thing I wanted to ask is just if there’s anything else that you would like to say about this point in your career.

RP: Well, something I’ve probably said before, if you’ve been reading stuff I’ve said, is that this book is really different for me because… It’s simply that I got happy. My whole life, my whole sense of self-worth is not tied up into the impact of whatever novel I put out. I’m happy in a lot of different avenues of my life. And so the books have gone from, you know, “This is it, I’m putting all my eggs in this basket,” to one of the things in my life. So I don’t have the same anxiety, and I didn’t have the same anxiety when I finally did settle down to write. I wanted to keep my characters… I didn’t want to have 10,000 mini-climaxes and “Oh, I wonder what happens next!” I just wanted human people doing human things crossing in the night. And it’s different for me. There’s no “We gotta find out who did it.” The police presence in this book is as much the domestic life of this [character] Mary Roe as it is finding this guy and trying to figure out what’s the story with the main character when he starts giving talks. On that level, there’s no solving to be done. In fact, when she’s looking for this one guy that’s missing from the building that she’s obsessed with, as you know, she goes from pillar to post, from pillar to post, pillar… And then he just shows up. And that’s it.

I have heard you talking about that, and yeah, as someone who enjoys your work and also relates to a lot of the anxiety that runs through a lot of it, it’s very gratifying to me to hear you say that. And yeah, I think that’s present in the book as well.

RP: I don’t know who said it originally, but somebody told me… It sounds like Henry James said it or something: “Sometimes the greatest novels are the ones where the smallest event leads to the most revolutionary change in a character,” as opposed to a gigantic event. Something Edith Wharton-esque or something like that. For a couple of books, I was seeing a shrink, and his favorite books, of course, were Jane Austen, George Eliot and Henry… He was like, “Eh” about my books because he thought they were too spectacular, spectacle-like.

Your therapist was criticizing your work?

RP: Well, that’s his job. I mean, to tell me what he sees and what he thinks is going through my head that I have to do a certain thing. Oh, that was the least of it.

So yeah, I feel like this book is different. I’m kind of happy with it, but give me a couple of years. I’ll look back and I’ll go, “Oh my God, how did I get away with that?” Which is what happens.

***

Thanks to Richard Price for taking the time to speak with me again. Lazarus Man is in stores now!